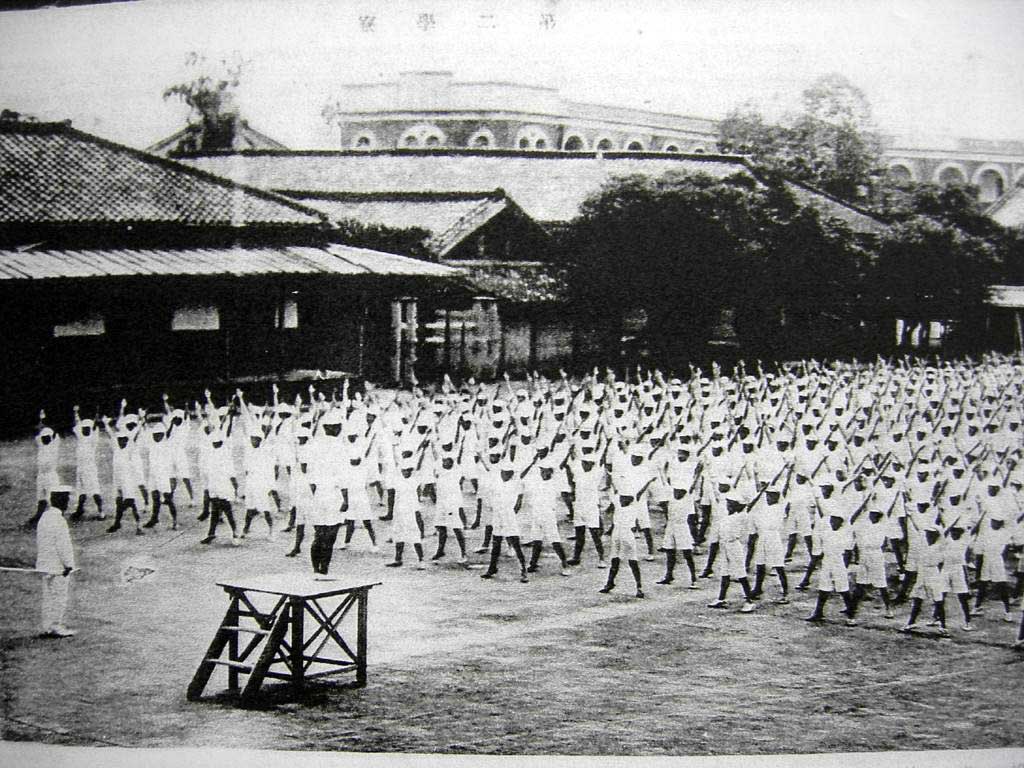

As mentioned previously, the practice of sound governance in Taiwan began as early as the Japanese colonial period. In addition to restricting the broadcast and release of Taiwanese operas and pop songs so that assimilation policy could be effectively implemented, the Japanese colonial government broadcasted the “radio calisthenics” accompanied by music and guidance on the radio in every household around Taiwan, calling “all people on this island” to raise hands, bend over, and lift legs in a synchronous manner. In other words, the Japanese colonial government harnessed the power of sound apparatus to profoundly reshape Taiwanese people’s perspective of time and corporeality.

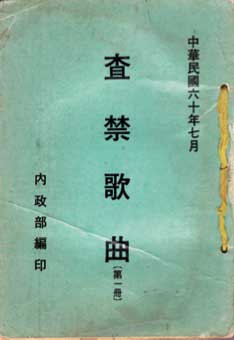

In the post-war era, the Nationalist government did not remove the ban on specific songs. It even imposed stricter censorship on pop songs in terms of lyrics and melody for the purposes of ideological control. By the late 1980s when music censorship faded into history, sound governance gradually took a neoliberal turn—the public broadcasting and performance of a song was regulated by copyright law. The origin of this trend can be traced back to the early 1980s: under the relentless pressure of the U.S. trade retaliation, the Executive Yuan proposed “liberalization, internationalization, and institutionalization” as the guidelines on economic development in 1984. Later, the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) was established, and Taiwan was included by the U.S. in the Priority Watch List of the Special 301 Report. Subsequently, the five leading transnational record labels entered the Taiwan market, and the concept of sound as “private property” was thenceforth developed.

By the late 1980s, the music censorship faded into history. (source: Wikipedia)