Rainy Night Flowers

Taiwan

Rainy Night Flowers and Sound Apparatus as Historical Narrative

As a contribution to the exhibition Sound Meridians, artist Chao-Ming Teng’s work After All These Years, recounted the turbulent history of Rainy Night Flowers, the longest-living pop song in Taiwan. The song’s circulation path and duration were turned into visible objects in Teng’s narrative. According to his interpretation, there is a key reason why Rainy Night Flowers has enjoyed such enduring popularity: it has been “relayed from generation to generation”, ensuring its survival to date. Here, we may look at this issue from an alternative angle. No sooner was Rainy Night Flowers released than it reached a surprisingly wide audience, largely because it was one of the earliest “pop songs” in Taiwan produced in the form of record. The so-called “pop song” is in essence a musical genre responding to the invention and commoditization of the sound apparatus (e.g., microphone, gramophone, and radio) in the early 20th century. It is more than a musical form insofar as it is a new paradigm of music production. The musical forms created as a result of the invention of new technologies played a vital role in the 20th-century history of music. For example, the invention of electronic guitar gave birth to rock and roll, and that of drum machine brought about techno. A clarification of the problématique is necessary before further discussion on the “sound apparatus.” Why should we care about “sound apparatus”, apart from its function of incubating new musical genres and paradigms? We may treat the broadcasting system, the first electronic sound apparatus in the world, as the starting point for our thinking. Audio broadcasting was invented in 1906, and the first commercial radio station in the world was founded in The Hague in 1919. Later, futurists issued the manifesto La Radia in 1933, in which they described broadcasting as a medium having limitless potential and capable of terminating all traditional art forms. To put it another way, the space-penetrating power of sound transmission provided artists with a creative tool of infinite possibilities—it demarcated a boundary between traditional and modern art. On the other hand, VE-301, the Volksempfänger (lit. people’s receiver) developed by order of Paul Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda of the Nazi Germany, also appeared on the market in 1933 with an affordable price for general laborers. Although commercial broadcasting systems had already been run in the United States and Europe at that time, Goebbels was the first person who found its potential as a political propaganda tool and used it to the maximum. He noticed that Hitler’s audience in the largest assembly were at most tens of thousands in number, and he thought that the people would be easily united and bent to Hitler’s will if each German household is equipped with a radio. We can see how sound apparatuses were employed in forging people’s emotional bonds and affecting their perception from the vicissitudes of Rainy Night Flowers. Composed in 1934, this song raised Taiwanese consciousness at that time. However, in 1938, it was specially adapted for Honorable Soldiers, a song used for recruiting Taiwanese people to serve the Armed Forces of the Empire of Japan. That is to say, in the modern sound culture, the process from utterance to listening involved not only electric waves, machines, or sound wave storage devices such as records and cassettes, but also the invisible power and politics aimed to prohibit or promote particular voices. Sounds can disseminate messages as well as carry and shape emotions, which was why sound apparatus inevitably became a tool and a weapon that all parties competed for. Following this train of thought, how should we frame the discussion on “sound apparatus?” First of all, the sound “apparatus” should be a sound-transmitting “object” that transcends the physical confines of space-time. Secondly, this concept implicates not only technological objects but also the concomitant operational mechanisms, institutions, regulations, and production systems. For instance, the emergence of records entailed not only record labels that produce them and record stores that peddle them, but also “sound industry systems” such as the laws and institutions that manage copyright. Under this definition, we can try to chart the progress of Taiwan’s modern sound culture by reference to its history. We investigate the history of sound apparatus in Taiwan, so that we can trace its evolution and the power struggles it was enmeshed in. In this exhibition, we presented The Evolution of Sound Apparatus in Taiwan, a chronology of significant political situations and events that provides three major contexts for the visitors to piece the sound apparatus together.

-

- Posted by ctadmin

This chronology pays particular attention to the evolution of sound culture from its quantitative to qualitative change induced by the popularization of technological objects. For instance, Telecaster was a kind of solid-body electric guitar produced since 1950. As a type of electronic musical instrument featuring mind-blowing volume and peculiar sound...

-

- Posted by ctadmin

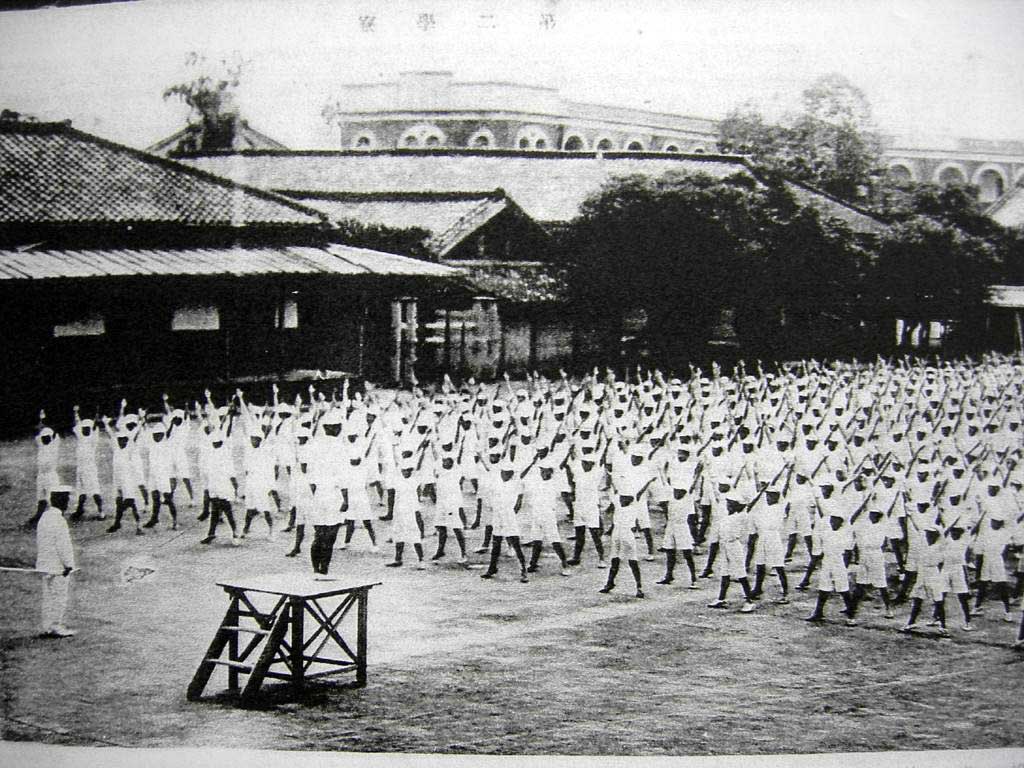

As mentioned previously, the practice of sound governance in Taiwan began as early as the Japanese colonial period. In addition to restricting the broadcast and release of Taiwanese operas and pop songs so that assimilation policy could be effectively implemented, the Japanese colonial government broadcasted the “radio calisthenics” accompanied by...

-

- Posted by ctadmin

This chronology began with the year of 1928 when the first radio station in Taiwan—Taipei Radio Station—came into operation. The station was established by the Government-General of Taiwan, followed by the inaugurations of its counterparts in Taichung, Tainan, Minxiong, and Hualien. The contents broadcasted at that time were mainly in...

Jeph Lo

As a researcher in the field of sound culture and the co-founder of TheCube Project Space (Taipei-based, non-profit), Jeph Lo has devoted long-term attention to the development of indie music, experimental music, as well as sound art and culture in Taiwan. He used to write special reports on the thriving indie music in Taipei for weekly and periodicals in the 1990s. He edited Walk the Music: Taipei Music Map since ‘90 (2000) and translated Altered State: The Story of Ecstasy Culture and Acid House (2002). Besides, he co-curated the exhibition Altering Nativism: Sound Cultures in Post-war Taiwan (2014) and worked as the chief editor of the exhibition’s catalogue/reader. Moreover, he is the chief organizer of the website Soundtrack: The Database of Taiwan’s Sound Culture (soundtraces.tw) and the Talking Drums Radio streamed online.